The real Living Wage is a voluntary UK wage rate based on the cost of living, paid by over 15,000 UK employers. The Living Wage rates are independently based on what people need to meet the costs of living. Outside of London it is currently £12 per hour and within London it is £13.15.

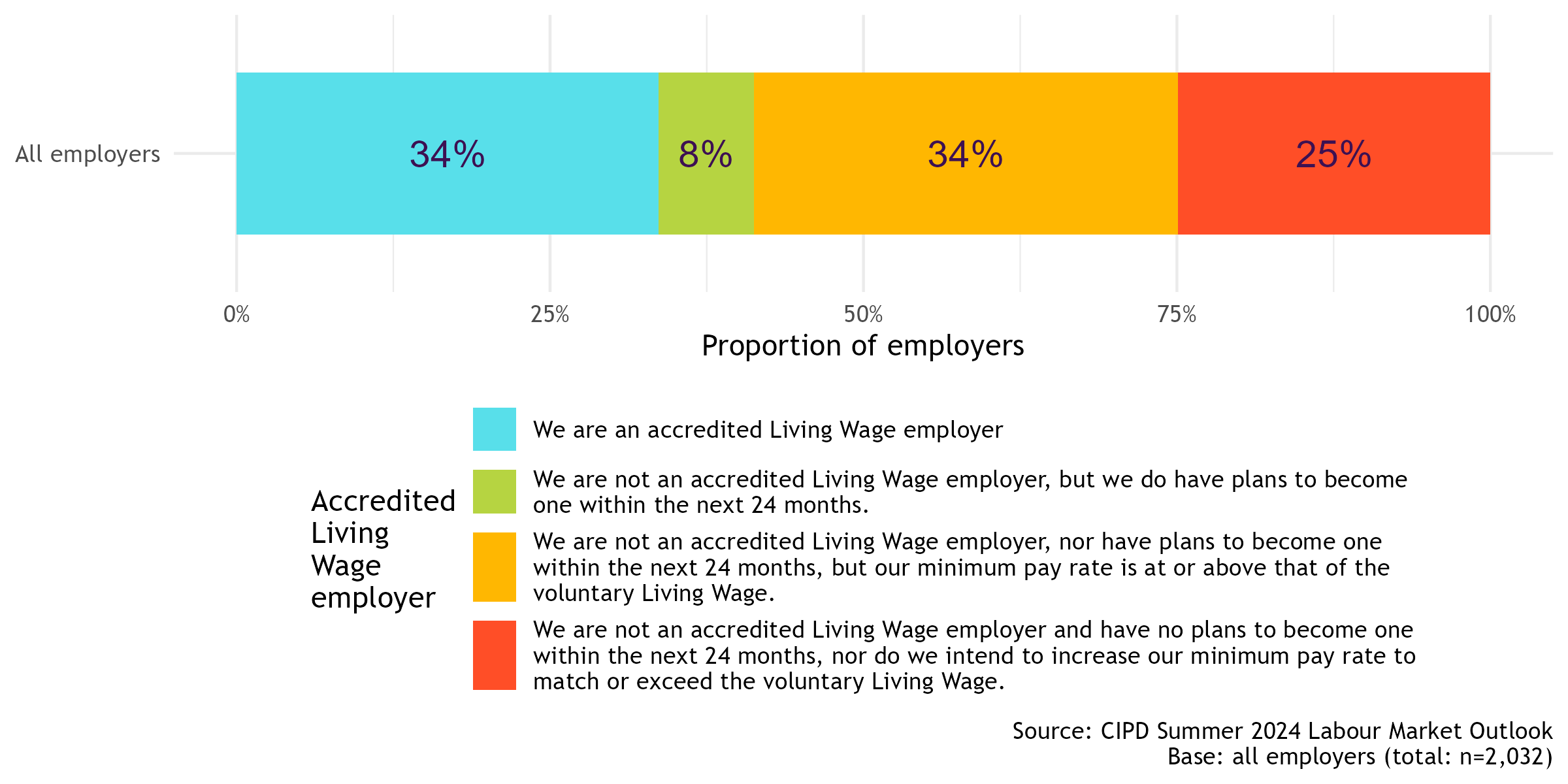

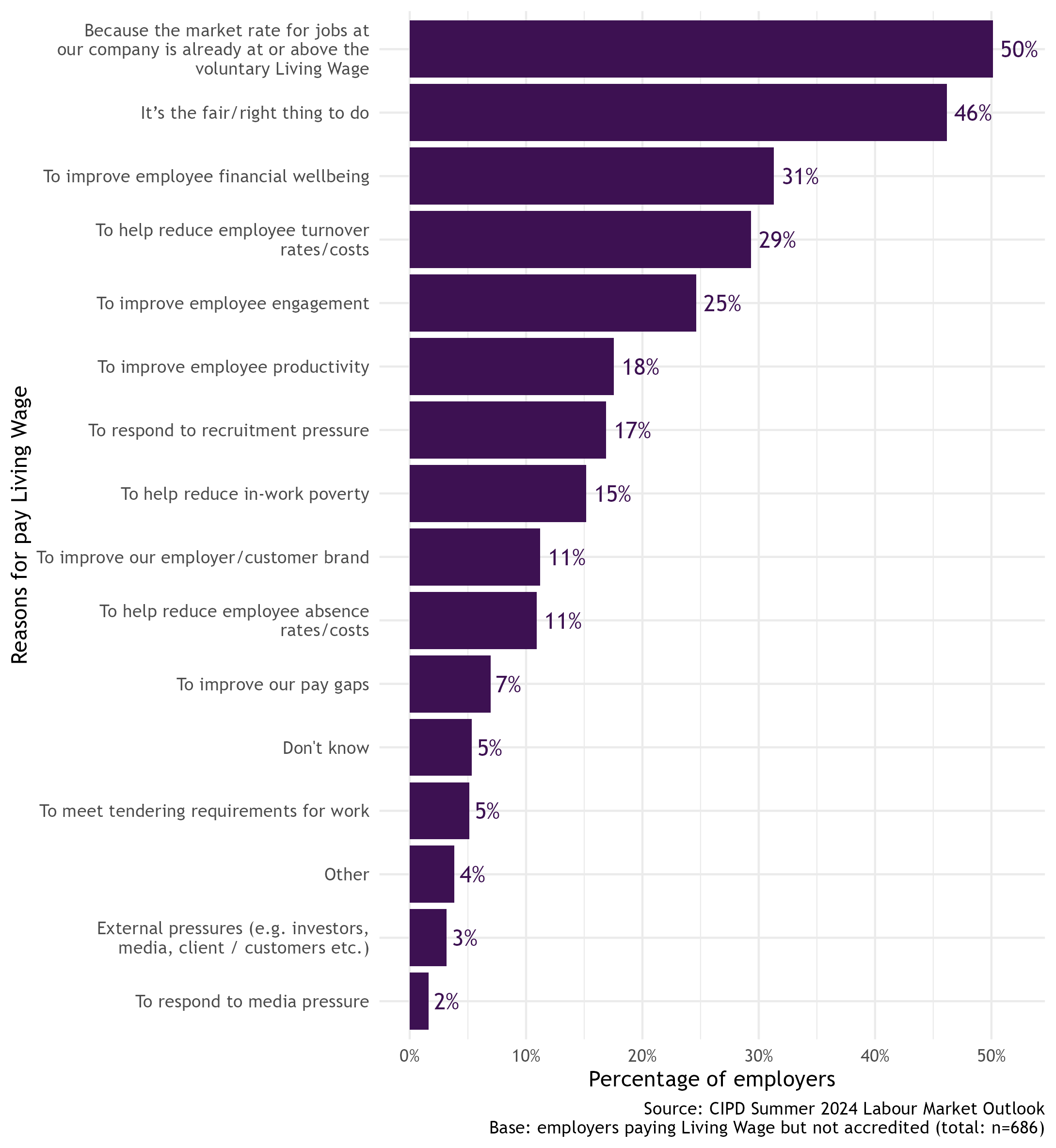

More than a third (34%) of respondents to the CIPD’s Labour Market Outlook – Summer 2024 survey said their workplace was an accredited Living Wage employer (Figure 1). This proportion is virtually the same as last year (35%), but higher than in summer 2022 (29%).

No substantial change to proportion accredited as Living Wage employers

Figure 1: Accredited Living Wage employers

Accreditation is higher in the public (46%) than in the private (31%) or voluntary (30%) sectors. Within the private sector, accreditation is higher in manufacturing and production (41%) than among service firms (27%).

Then within private sector services, nearly half (47%) of all respondents in the transport and storage sector said that their company was accredited, higher than 36% last year and 24% in 2022. The sector with the next highest proportion of accredited firms is information and communication with 42%, up from 32% a year ago, followed by finance and insurance at 39%.

In terms of business size, there is a marked difference between large firms and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The proportion of accredited large firms (250 or more workers) is three times that of accredited SMEs (1–249 employees) (45% vs 14%).

Why do employers become Living Wage employers?

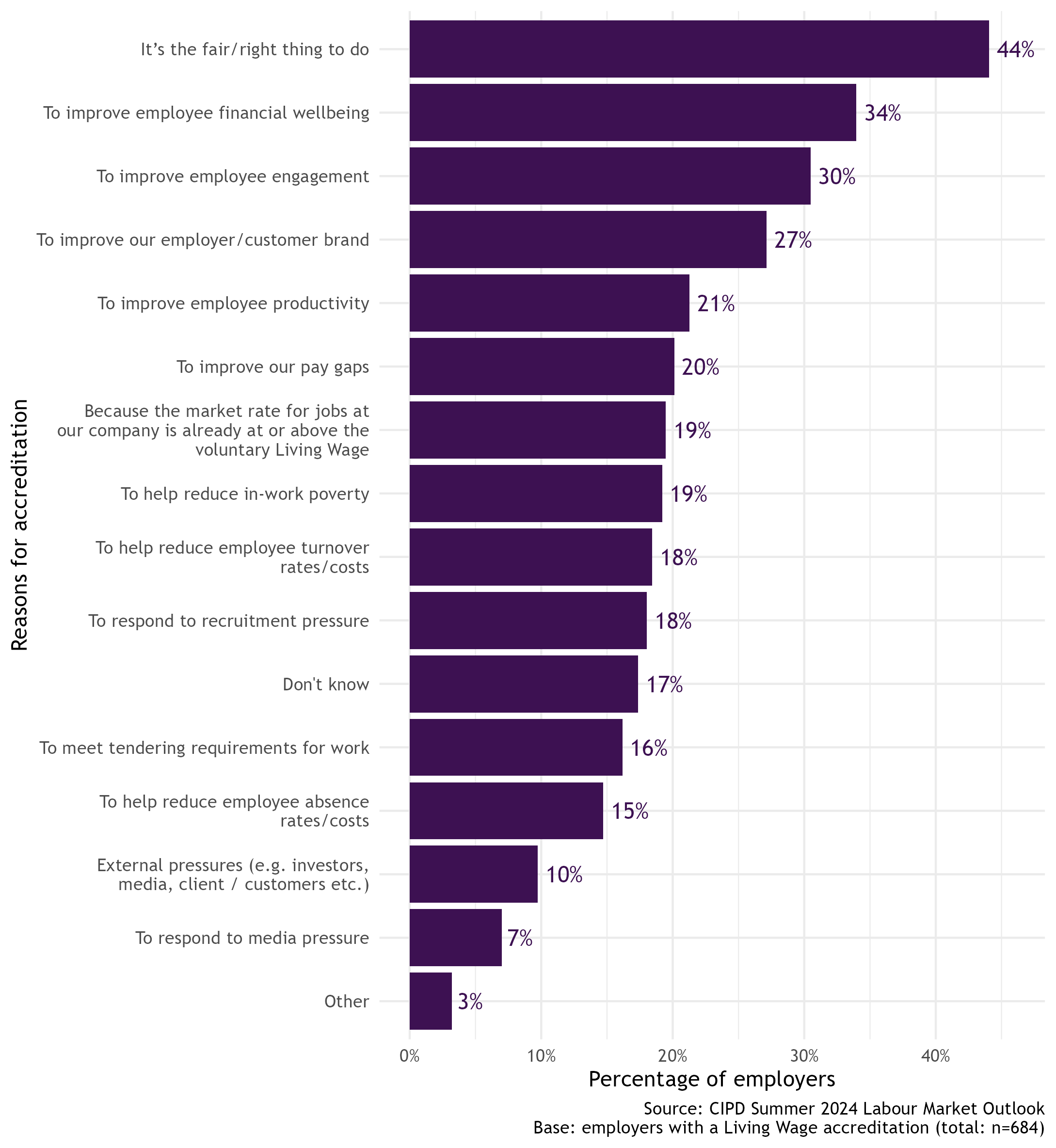

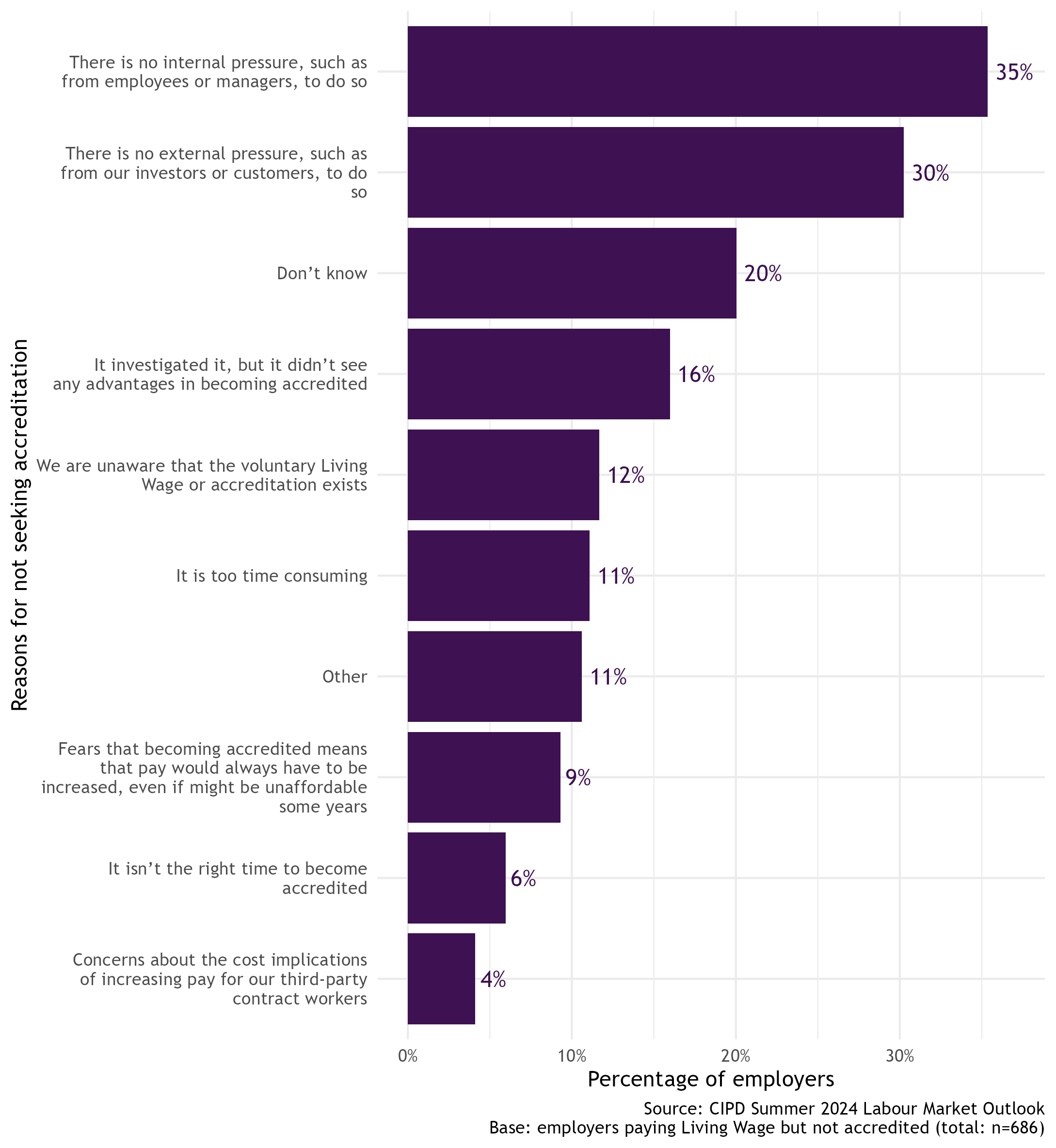

The survey results show that the main reason employers commit to the Living Wage (Figure 2) is because they believe it’s the fair/right thing to do (44%). Some reasons are more common now than 12 months ago; for instance, 30% of employers have become accredited to improve employee engagement, compared with 24% in 2023. The proportion of those becoming accredited to improve employer/customer brand has also risen, from 21% to 27% over the year. Meanwhile, 18% of employers became accredited in response to recruitment pressure, compared with 14% last year.

Main reason for accreditation is because ‘it’s the right thing to do’

Figure 2: Reasons for accreditation among Living Wage employers

However, 17% of respondents were unable to explain why their organisation had become a Living Wage employer – more commonly among large firms (20%) than SMEs (4%). One plausible explanation is that these employers have been accredited for so long that the original reasons for doing it may have been forgotten – the real Living Wage was first introduced in 2011.

Large companies (37%) were less likely than SMEs (50%) to sign up to the Living Wage because it’s the fair/right thing to do, but they were almost as likely (36%) as SMEs (38%) to do so to improve employee financial wellbeing. Compared with SMEs (24%), large employers (34%) are more likely to sign up to improve their employer/customer brand. Becoming accredited to meet tendering requirements for work has been an increasing driver both for large companies (up from 13% last year to 20% in 2024) and for SMEs (up from 9% last year to 17% in 2024).

Public sector employers (47%) were more likely than private sector ones (39%) to have signed up because it’s the fair/right thing. But private sector firms were more likely (36% vs 25%) to say they had become accredited to improve employee financial wellbeing as well as to try and raise employee engagement (36% vs 19%).

Why are other employers looking to sign up?

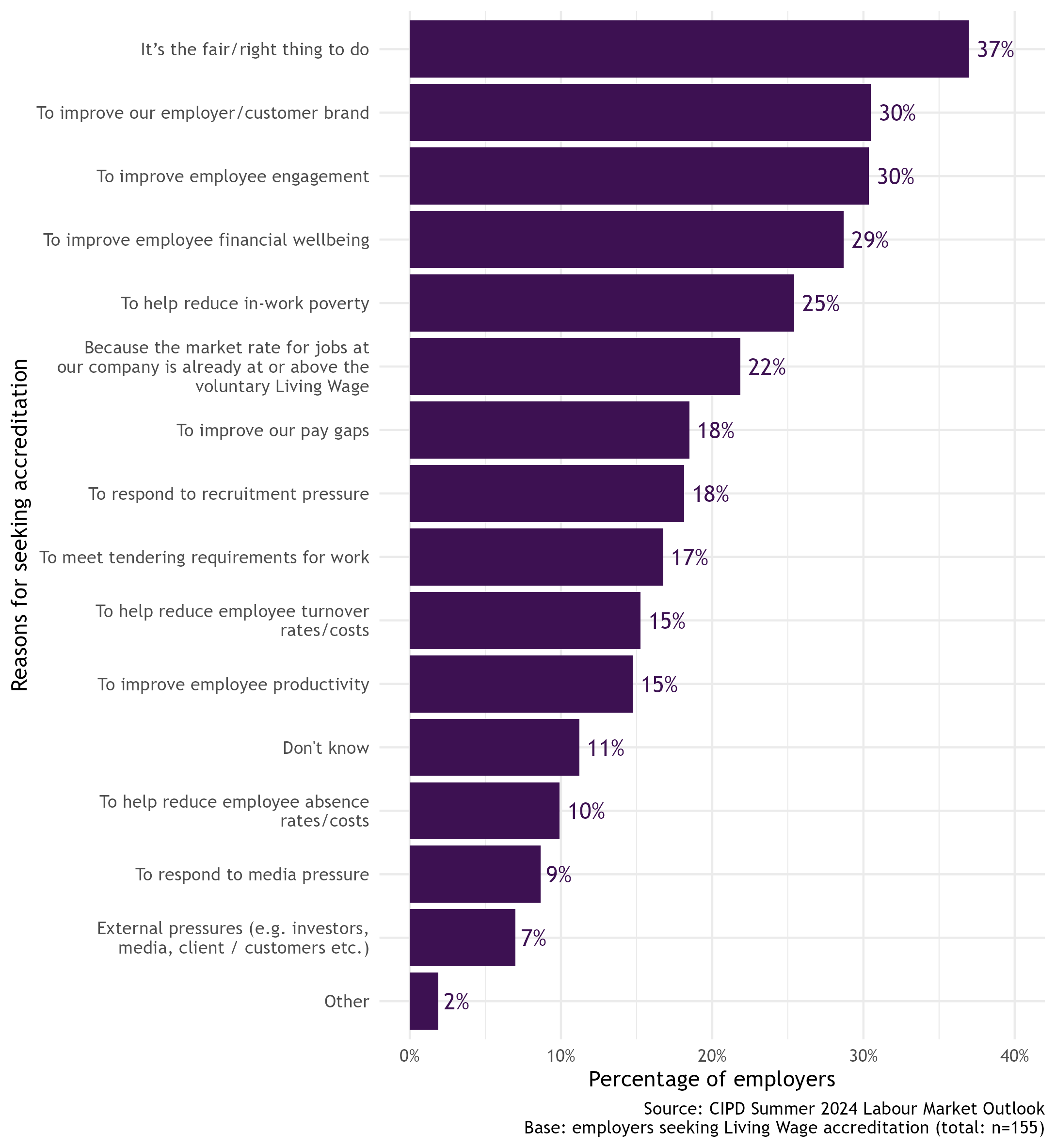

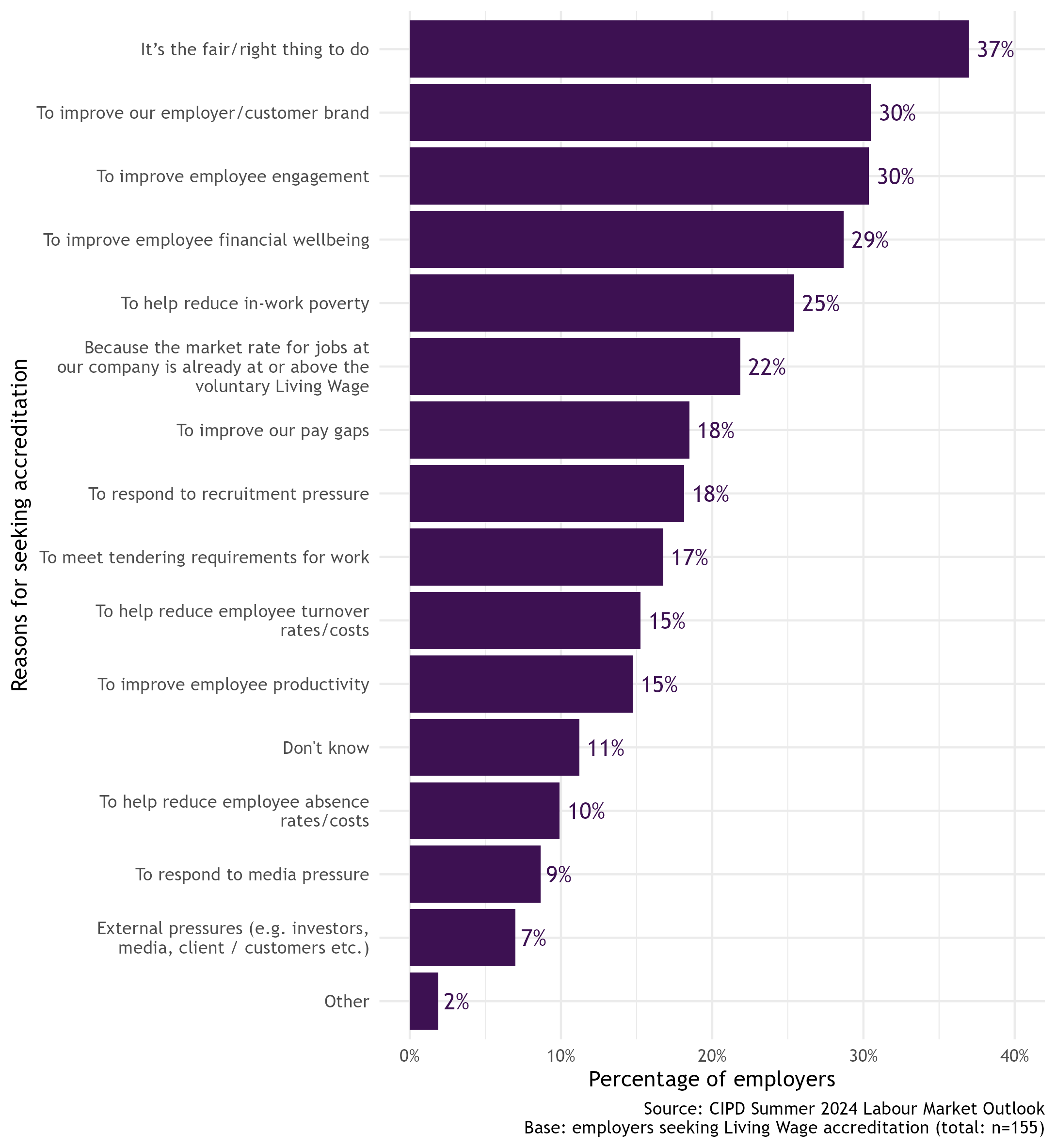

Our data found that 8% of unaccredited workplaces will seek accreditation over the next couple of years. The most common driver for doing this is because it’s the fair/right thing to do (37%) (Figure 3).

Similarly, seeking accreditation to meet tendering requirements for work is becoming more common, up from 13% last year to 17% in 2024.

Fairness most common reason for seeking accreditation

Figure 3: Reasons for seeking accreditation among non-Living Wage accredited employers

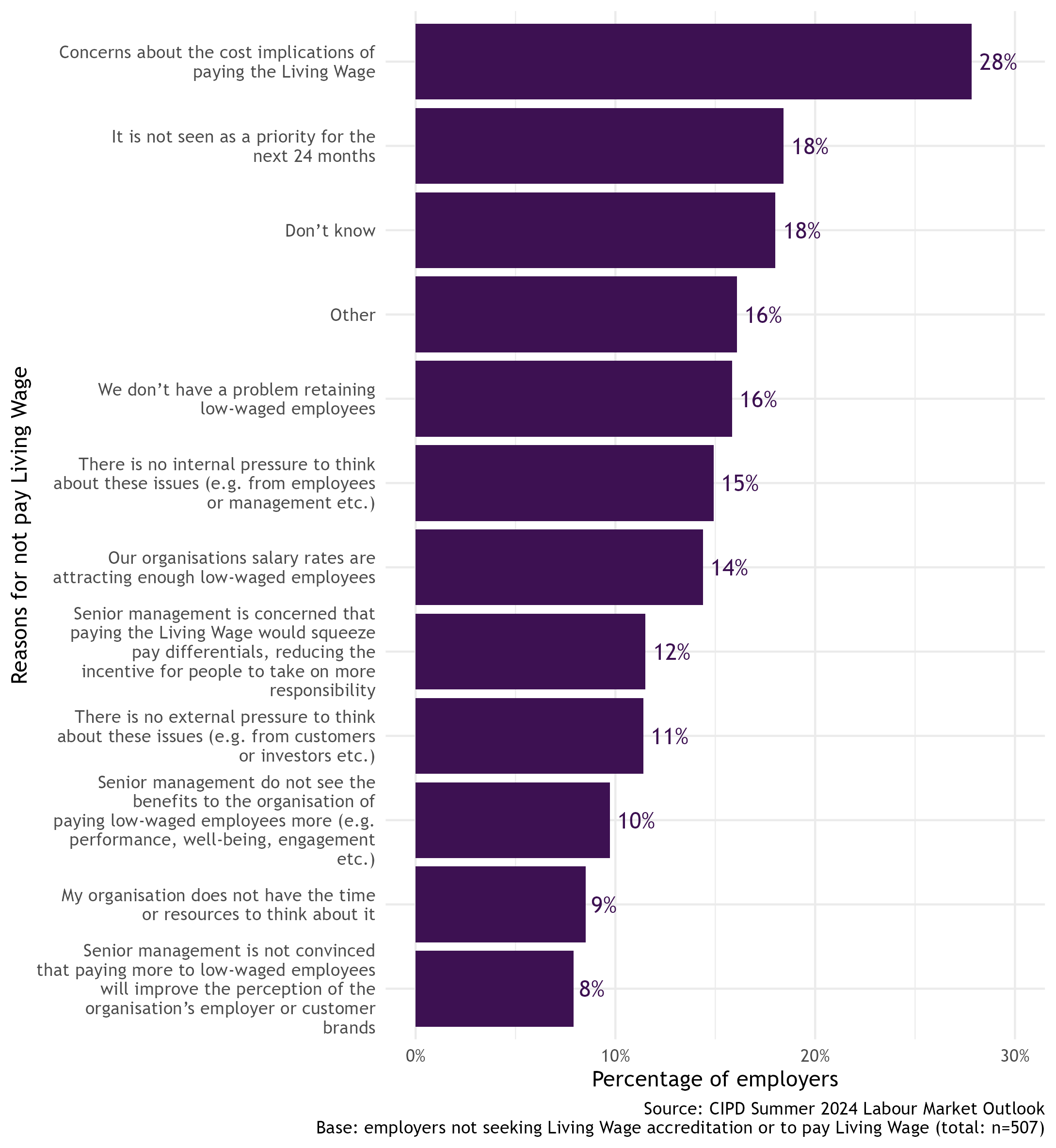

Why don’t some employers want to pay the Living Wage?

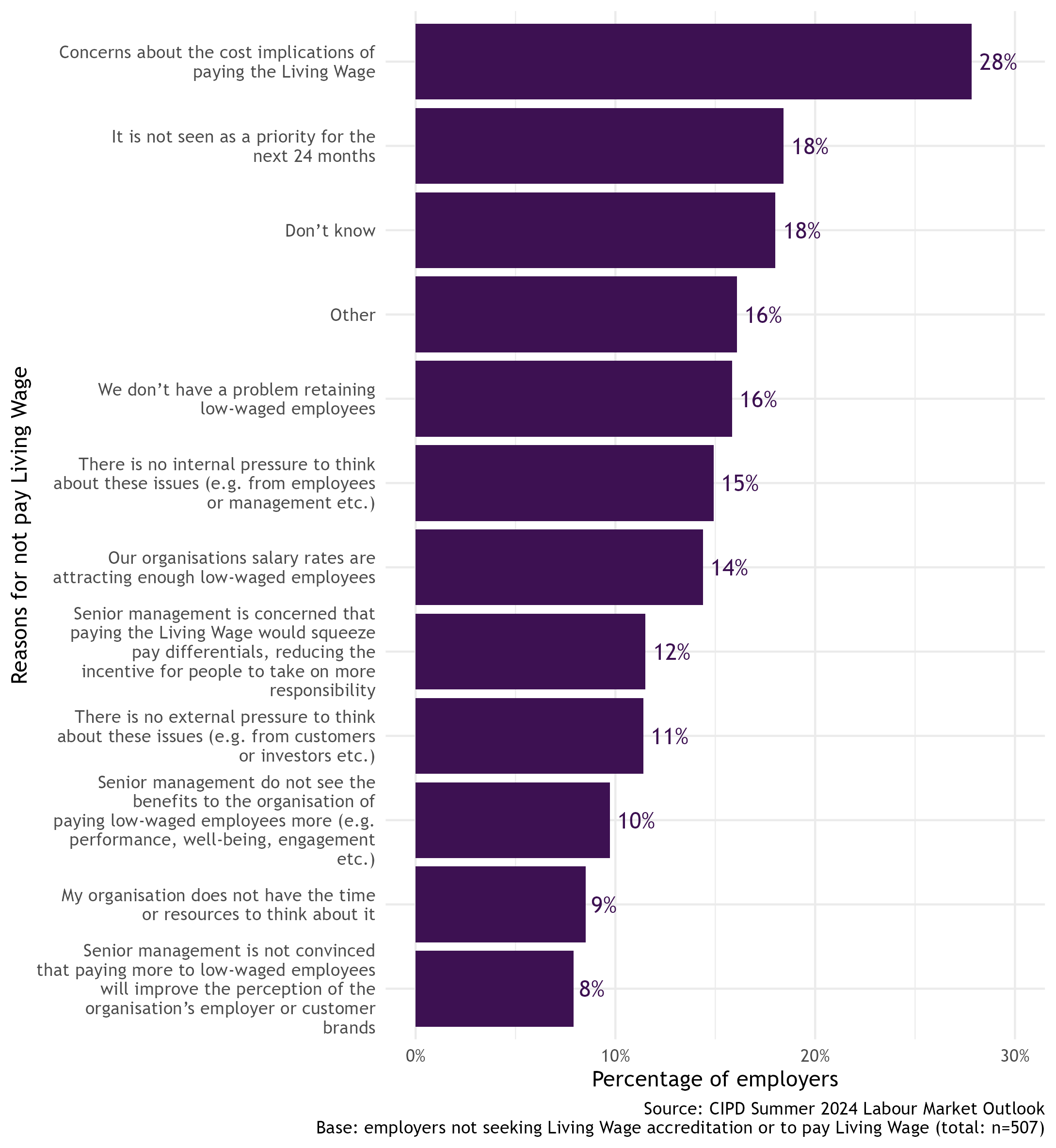

In our sample, 25% of respondents said their workplace has no plans to increase its minimum pay rates to match or exceed the Living Wage.

This view was more common in private sector services (30%), especially among SMEs (38%) and those businesses in the hotels, catering and restaurants, arts, entertainment and recreation sector (39%), or in the wholesale, retail, and real estate (34%) sector.

Figure 4 shows the most common reasons for not having plans to raise minimum pay to match or exceed the real Living Wage, such as concerns about the cost implications (28%).

However, 18% of respondents were unsure why their organisation had no plans to increase their minimum pay rates to match or exceed the Living Wage.

Cost implications is top reason for not paying Living Wage

Figure 4: Reasons for not paying Living Wage

Why don’t some employers want to become accredited?

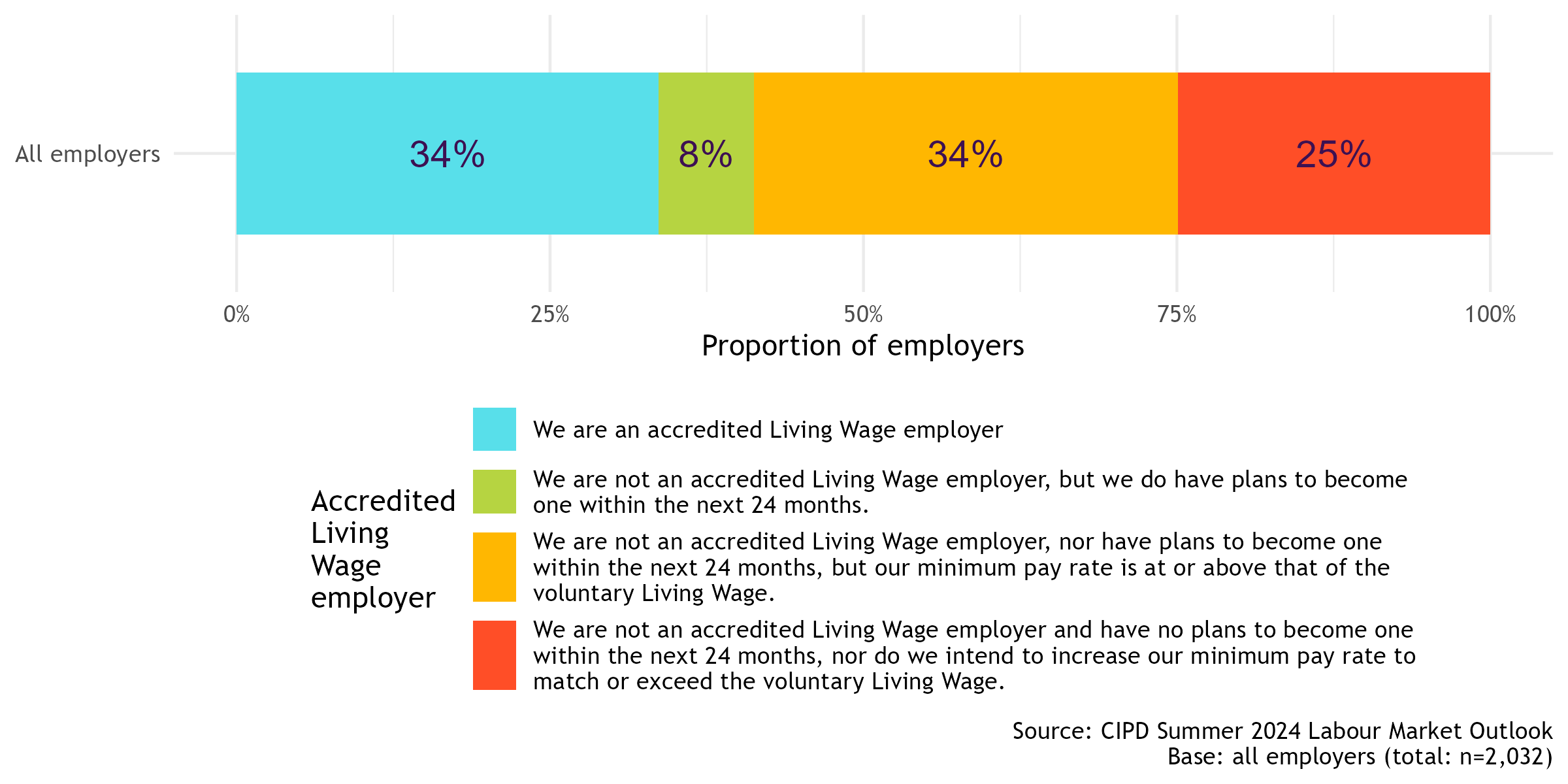

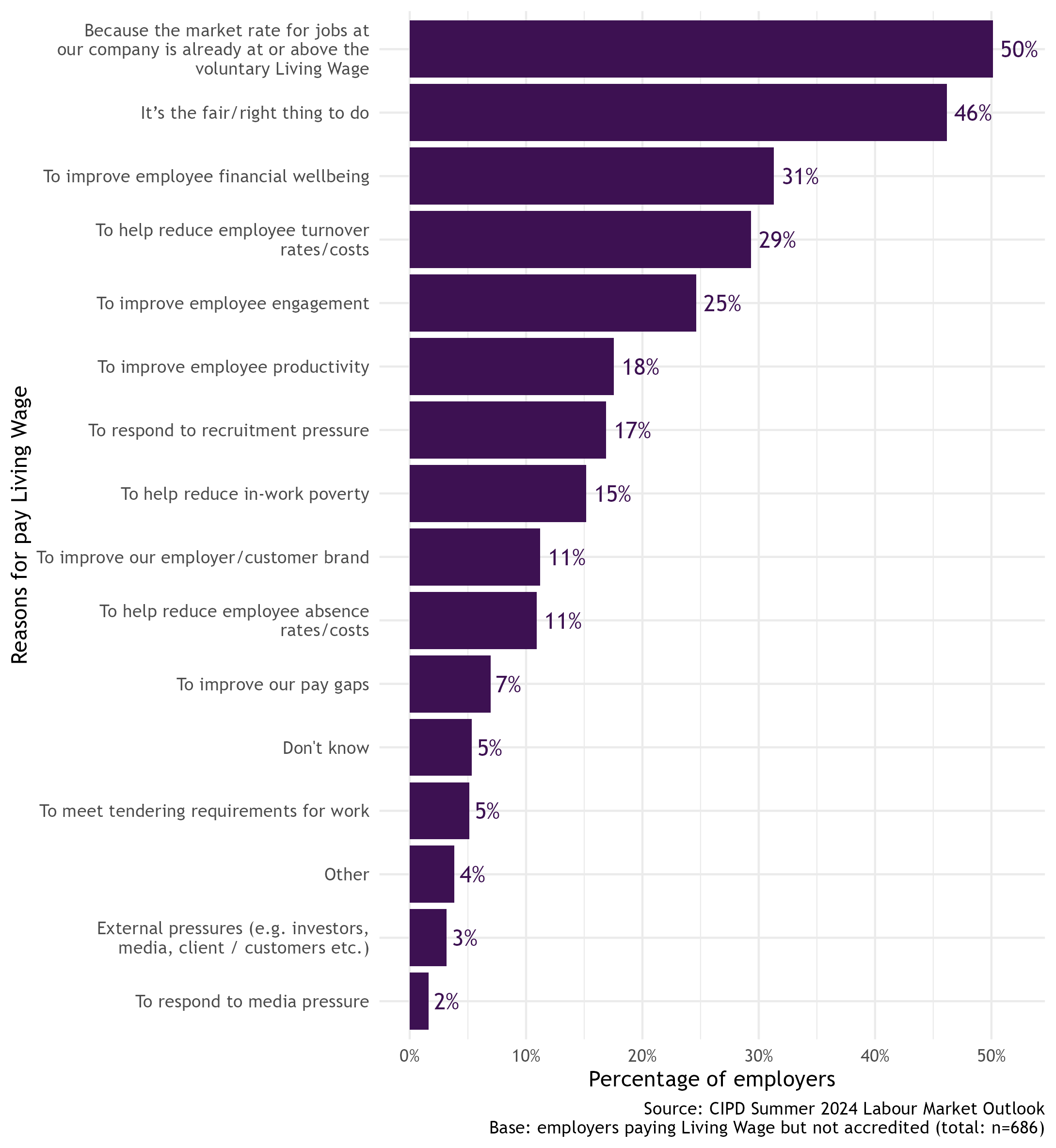

Finally, 34% of respondents said that although their organisation pays at or above the Living Wage rate, it was neither an accredited Living Wage employer nor was it seeking accreditation. Figure 5 shows the most common reasons for paying at or above the voluntary Living Wage.

Half of non-accredited employers already pay at or above Living Wage

Figure 5: Reasons non-Living Wage accredited employers pay the Living Wage

Compared with 2023, more employers said they pay at or above the voluntary Living Wage because the market rate for jobs is already at or above the Living Wage rate (42% in 2023 vs 50% in 2024). Fewer employers are paying at that rate in response to recruitment pressure (17% vs 24%) and to improve their brand (11% vs 16%) than 12 months ago.

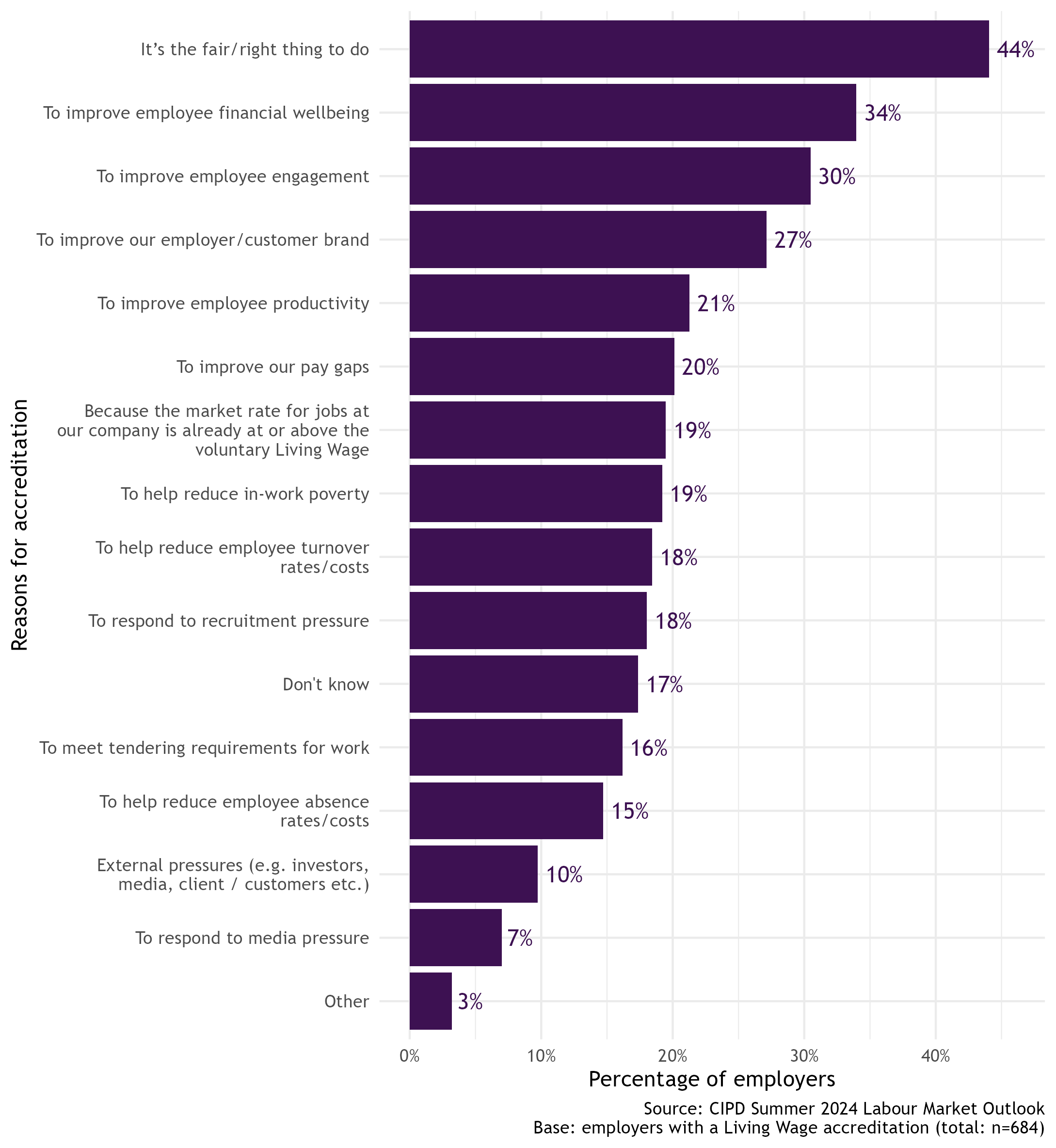

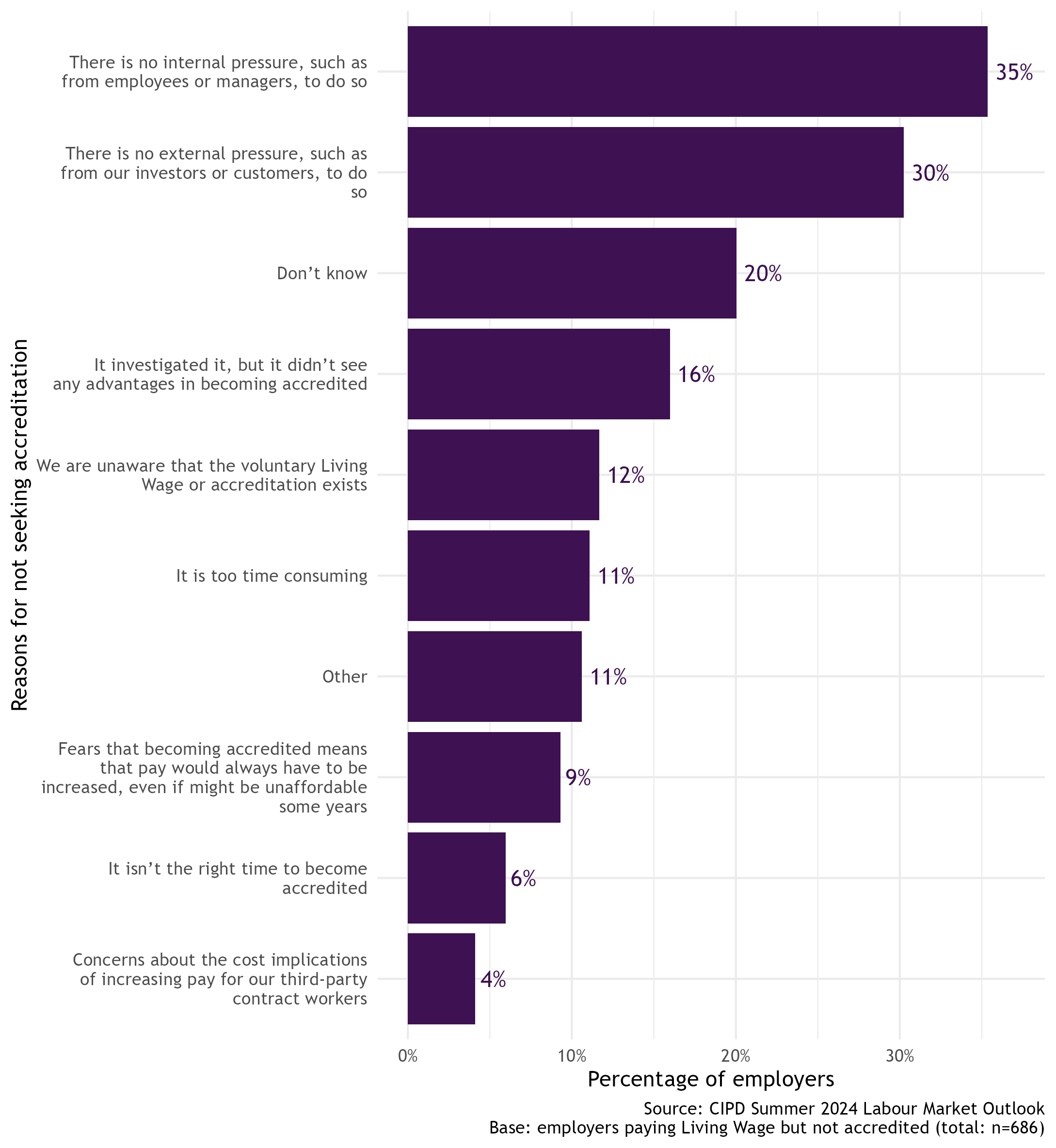

Figure 6 shows the reasons given by respondents as to why their organisation has not sought nor is seeking accreditation, despite them already paying at or above the Living Wage. The most common explanations were that there were no internal or external pressures to do so.

No pressure to seek accreditation

Figure 6: Reasons non-Living Wage accredited employers paying at or above Living Wage are not seeking accreditation

Again, 20% were unsure why their organisation had not signed up, a response more than twice as likely among large firms (25%) than SMEs companies (11%).

Implications and recommendations

While the cost of living is not increasing as fast as it had been, most prices are higher than they were a few years ago. Many low-waged workers are just a pay cheque away from falling into poverty.

But how can a business that does not already pay the real Living Wage afford to do so? An option is for the UK Government to cut business costs, such as reducing corporation tax or employer National Insurance contributions. However, given the state of public finances, this is unlikely, even though the government is committed to improve workplaces, jobs, and pay.

The other option is for such an employer to improve its own productivity so it can afford to increase wages.

One approach to kickstarting productivity gain is to bite the bullet and raise overall pay, perhaps starting with the lowest paid. The theory is that this will make it easier to attract and retain talent, which then feeds through into lower employee turnover costs, improved job satisfaction, higher levels of organisational commitment, and better employee productivity.

But this is a gamble because while it takes time to see improved productivity, pay costs jump immediately. Also, for higher wages to work their magic, the workplace needs to have both good people and business management practices in place, such as having fair pay decisions, or providing staff with the right equipment.

Another approach is by improving employee and business performance first. By investing in technology, products and marketing, as well as in people skills and management, employee and company performance should rise. The additional profit generated by higher revenue and lower costs then allows the firm to increase pay for low-waged staff.

Yet this is also a gamble, because it takes time for productivity to increase and wages to improve. Low-waged employees may not feel committed or engaged in their work if it is taking time for their improved performance to result in higher wages, and so they leave for better pay elsewhere. Also, success will depend on the firm having the right business and people management practices.

However, these approaches are not binary. People managers should consider how much the firm should spend on increasing pay and how much to spend on improving productivity. Also, the government can play a part in helping to boost workplace and business performance, so that employers can afford to pay more, such as by investing in AI, improving employee relations, and simplifying the planning process. It should also explore how its procurement requirements encourage employers to pay their people enough to live on.